T

welve years ago, shortly after winning his third consecutive general election, Tony Blair gave the Labour party a brief lecture on economics. “There is no mystery about what works,” he said, crisply, speaking from a podium printed with the slogan “Securing Britain’s Future” at the party conference in Brighton. “An open, liberal economy prepared constantly to change to remain competitive.”

Blair rounded on critics of modern capitalism: “I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer. They’re not debating it in China and India.” He went on: “The temptation is … to think we protect a workforce by regulation, a company by government subsidy, an industry by tariffs. It doesn’t work today.” Britain should not “cling on to the European social model of the past”.

Most of his conference speech was vigorously applauded. But the passage on economics was received with solemn looks and silence. There was no heckling, as there had been when previous Labour leaders and chancellors delivered what they saw as home truths about the economy. Instead, there was a sense of resignation in the hall: an acceptance by a party of the left that the right had won the economic argument.

In the early years of the 21st century, the inevitability of an ever more competitive, deregulated, internationally orientated market economy, to which both government and society were subordinate – a doctrine often called neoliberalism – was accepted right across the mainstream of British politics: from the Thatcherites who still dominated the Conservative party; to the increasingly pro-business Liberal Democrats, who would soon form a coalition government with the Tories; to the Scottish National party, whose then leader Alex Salmond praised Ireland and Iceland for their low corporate taxes; to the Blair cabinet itself, where, I was told by a senior Labour figure in 2001, “You won’t find a single member with anything critical to say about capitalism.” It was assumed by the main parties that most voters felt the same way.

Margaret Thatcher’s government had overcome fierce opposition to install a free-market economy in Britain. But under Blair, seemingly more consensual and less dogmatic, the extending of markets into ever more areas of everyday life was presented as unavoidable, or simply practical: “what works”. The British housing market was thriving, with home ownership reaching an all-time high in 2003. There had not been a recession since 1991, a blissfully long time for the previously fitful British economy. Compared to the sometimes tatty, depopulating country of the 70s and 80s, much of Britain in the early 2000s looked successful – a society of regenerating city centres and steadily rising wages.

The free-market ascendancy was acknowledged even by some of its strongest critics. In 2000, the Marxist historian Perry Anderson declared: “The only starting-point for a realistic left today is a lucid registration of historical defeat … Neo-liberalism as a set of principles rules undivided across the globe: the most successful ideology in world history.” In 2007, Naomi Klein wrote in her book The Shock Doctrine that capitalism was “conquering its final frontiers”.

In 2017, that aura of invulnerability has evaporated. Disenchantment with the economic status quo has been potently expressed in elections across the world, from France to the US. But in no democracy has the political shift against the free market been as stark as in Britain.

Since Thatcher’s election in 1979, Conservative and Labour governments have privatised and deregulated, reduced taxes for business and indulged its excesses, opened up the economy to foreign capital and commercialised the national psyche, until Britain became one of the world’s most thoroughly neoliberal societies. And yet, at last year’s EU referendum, the votes of those “left behind” by all this played an unexpectedly pivotal role. Then, at this year’s general election, both the Conservatives and Labour campaigned – or appeared to campaign – against the economic system that they themselves had created.

The Conservative manifesto attacked “aggressive asset-stripping” of British companies by foreign buyers; “perverse pricing” by privatised rail companies; “exploitative” markets in energy, property, insurance and telecommunications; and “the remuneration of some corporate leaders … [which] has risen far faster than some corporate performance”.

“We reject the cult of selfish individualism,” the manifesto declared, in language seemingly calculated to insult Thatcherites. “We do not believe in untrammelled free markets.” Instead, the Conservatives now believed that “regulation [was] necessary for the proper ordering of any economy”. They would “enhance workers’ rights and protections”, and create an “economy that works for everyone”. The obvious implication was that the free market had created the opposite.

The Labour manifesto opened with almost exactly the same words: “Creating an economy that works for all”. Like the Tories, Labour attacked executive pay and promised to strengthen workers’ rights. Like the Tories, they offered an “industrial strategy” through which government – long depicted by free-marketeers as largely irrelevant or actively harmful – would help modernise the economy. And like the Tories, Labour said companies should no longer be run primarily for their shareholders, as free-market doctrine has insisted since the early 80s, but also for the benefit of their employees, customers and the public as a whole.

While the Conservatives offered mostly rhetoric, Labour offered policies – nationalisation, restored trade union rights, restrictions on the City of London – which would undo much of British neoliberalism. It is these policies that, on 8 June, helped Labour achieve its largest vote since Blair’s landslide in 1997, and now leaves the party possibly on the verge of power. John McDonnell, who lists one of his recreational activities in Who’s Who as “generally fermenting the overthrow of capitalism”, could soon be chancellor.

Amid all the current political turmoil in Britain and the wider world, the shift against free markets has yet to register fully with much of the media or many voters. But the most ardent neoliberals have noticed. “Free marketeers have been gobsmacked,” says Mark Littlewood, director of the Institute of Economic Affairs, which has supplied British politicians with pro-capitalist arguments for 62 years. “Things we thought of as like the laws of gravity are now up for grabs.”

The end of the free-market monopoly in British politics is part of an even bigger change. After almost a quarter of a century when it was widely agreed that the fundamentals of the economy were too important to be meddled with by politicians, or be subject to democratic scrutiny, the contest to shape that economy has restarted.

O

ne clue as to why Britain fell out of love with the free market is in the tone now adopted by its defenders. Gone is the capitalist triumphalism of the Thatcher and Blair eras. Instead, there are apologies. “Markets can be brutal,” concedes the Conservative MP James Cleverly, leader of the Free Enterprise Group, a Commons pressure group with three dozen members (all Tories) that was founded in 2010. “The benefits of free markets have not spread themselves between the generations as equally as many of us would like,” he says. “Part of the reason Corbyn got so much support in the election, for policies which I regard as economically illiterate, is that many people don’t value the impact my kind of economic values have had on their lives. The big wins we had with market reforms in Britain were back in the 80s.”

These days, many free marketeers are highly critical of how British capitalism operates. “The City is incorrectly incentivised,” says the Tory peer Nigel Vinson, who has been a leading player in Britain’s free-market thinktanks since the formative days of Thatcherism in the mid-70s. “We have sold far too many companies to foreign owners. A lot of corporate takeovers are personal megalomania, not corporate efficiency. There are abuses of market power, such as [the zero-hours employer] Sports Direct. Meanwhile you see [the advertising executive] Martin Sorrell taking home £70m in 2015. That sets a rotten example.”

Littlewood lists other dysfunctions: “Wage stagnation, poor GDP growth, crony capitalism in the contracting-out of public services, endless gaming of the system by corporations, a general ennui about the prevailing economic system … ” Finally, he cites the event that did more than any other to discredit free-market capitalism in Britain: “the 2008 crash”, the banking crisis caused by the deregulation and hubris of the financial markets.

That crisis and what followed – recession, prolonged weak growth, ballooning public and private debt, and seemingly endless austerity – has already destroyed or severely damaged the governments of Gordon Brown, David Cameron and Theresa May. It has necessitated contortions that suggest an economic system on life support: bank bailouts, unprecedentedly low interest rates, and quantitative easing – ie the Bank of England simply printing money and pumping it into the economy.

“The architecture of neoliberalism has had huge holes blown in it,” says Will Davies, reader in political economy at Goldsmiths, University of London. He argues that free-market capitalism has suffered a two-stage collapse: “First, in 2008, it was revealed as financially unviable. Then, in 2016 and 2017, it went into political crisis.” One symptom of the latter, he says, has been a rupture between big business and the main British political parties.

But this is not the first time that the economic failings and social costs of neoliberalism have led people to forecast its demise. Repeatedly in the past three decades, critiques and alternatives have been conceived and promoted, refined and combined by innovative thinkers and politicians of both main parties – and then frustrated and largely forgotten, until the re-emergence of many of their themes and advocates under May and Corbyn.

In the meantime, the free market has survived, and worked its way into more aspects of Britons’ daily lives, becoming in many ways progressively more efficient and thorough in its commodification of our activities, our homes, our minds. In fact, it might be this inhuman efficiency, and its social consequences, that has provoked the current political revolt against modern capitalism.

Is this revolt just another episode in a long resistance to neoliberalism, or is it a breakthrough? And if so, do Labour or the Conservatives have another viable economic model, which might make capitalism less dominant in our lives?

T

he first chance to change the economic order that Thatcher and John Major’s governments had imposed on Britain came 22 years ago. In January 1995, a few months after Blair was overwhelmingly elected Labour leader, the then Guardian economics editor Will Huttonpublished a panoramic book about the British economy, The State We’re In. Hutton had spent years exploring the economic ideas and social consequences of Thatcherism, and had decided that both were disastrous. He was a follower of John Maynard Keynes, the early-20th-century economist whose vision of a milder, state-regulated capitalism had shaped the postwar Britain that Thatcherism largely erased. Hutton was also close to the Labour party: two rising young Blairites, Yvette Cooper and David Miliband, gave him comments on the book’s manuscript.

The State We’re In depicted British economic life after a decade-and-a-half of Conservative free-market reforms as “meaner, harder, and more corrupting”. It also saw the economy as a failure in business terms: short-termist, low in productivity, over-reliant on the City of London and old technology, prone to boom and bust. Britain was falling behind other capitalist countries. “The individualist, laissez-faire values which imbue the economic and political elite,” wrote Hutton, “have been found wanting.” His solution was to import the best practices of other economies, particularly Germany, which he admired for its more patient, more socially inclusive economic approach. He called his vision “stakeholder” capitalism.

The book had a cautious initial print run of 3,500. But its timing was good: Britain was emerging sluggishly from a long recession, and was tired of Tory government. The State We’re In sold 250,000 copies, making it one of the bestselling economics books in Britain since the second world war. Among its readers were much of the New Labour government-in-waiting: Gordon Brown, Ed Balls, John Prescott, Robin Cook and Tony Blair himself.

“Tony was not a man of settled opinions, nor someone who knew a lot about economics,” says Hutton, “but David Miliband persuaded him to read it. This may be apocryphal, but apparently there is a picture of Blair reading it on holiday.” During 1995 and 1996, Blair’s speeches began to refer to the limitations of the free market, and to the desirability of a “stakeholder” economy, “run for the many, not for the few” – an almost exact prefiguring of the title of the 2017 Labour manifesto.

But then these themes were abruptly dropped. According to Hutton, as the 1997 election neared, Blair was told by his more nervous advisors that any talk of reforming British capitalism would be presented by the Conservatives as a return to the economic interventionism of the troubled Labour governments of the 70s. For decades, they had been crudely but effectively caricatured by the Tories, and much of the media, as bullyingly leftwing and disastrous. Meanwhile Brown, who as shadow chancellor had spent years trying to win over the City, decided Hutton’s book was too hostile to bankers; and Prescott, a Labour traditionalist, decided it was not anti-capitalist enough. “I was frozen out,” Hutton says.

In the late-90s, the economy started growing more consistently, as part of a technology-driven boom across the western world, and Hutton’s view of Britain began to seem too pessimistic. On winning power in 1997, Labour left most of the structure and practices of Thatcherite capitalism in place, and rather than question its rationale, they used swelling tax revenues to soften its social effects, for example through tax credits to subsidise low wages.

Outside Britain, the free market had more doubters. In 1997, the World Bank, previously an uncritical advocate of its state-shrinking orthodoxies, published a report conceding that “an effective state is the cornerstone of successful economies”. In South America, the failures of market-driven economic policies began to move electorates dramatically leftward. And in 1999, an even wider mass movement formed around the world against the environmental and social damage done by globalisation, as the spread of free-market capitalism was euphemistically called by its advocates. Enormous protests took place, from Genoa to Seattle. Smaller, but still vibrant, anti-capitalist demonstrations began to occur regularly in London.

But still most British politicians did not take them very seriously, regarding the movement as backward-looking and naively utopian. In a brief book published in 2001, the Financial Times journalist John Lloyd, a former communist who had become a New Labour associate, described the activists’ annual summit at Porto Alegre in Brazil as “a ragbag of declamation, hot air and vapidity”. The contempt was mutual: most of the protestors showed no interest in forming alliances with centre-left politicians in order to slightly civilise capitalism. “It’s not our job to suggest alternatives!” one prominent activist told me in 2000.

By the mid-00s, the protests were tailing off. Rather than listen to the anti-capitalists, the Blair government and its centre-left counterparts regulated their sometimes violent demonstrations with ever more riot police – while regulating the more powerful anarchic forces of finance capitalism less and less. The British public, meanwhile, seemed to have largely accepted the reign of the free market: during the mid-00s, the annual British Social Attitudes survey found that dissatisfaction with its impact on society and the workplace, while still substantial, had dipped to the lowest levels ever recorded.

With the economy still growing, year after year, the mass benefits of unfettered capitalism – ever wider property ownership, low inflation, cheaper consumer goods, and “no more boom and bust”, as Brown put it – appeared secure. “For most people under 20,” wrote the cultural critic Mark Fisher in his 2009 book Capitalist Realism, “the lack of alternatives to capitalism is no longer even an issue. Capitalism seamlessly occupies the horizons of the thinkable.”

And yet, even during these boom years there were signs that the free-market economy might be brittle. In 2001, the rail infrastructure company Railtrack – which had been one of the Conservatives’ most high-profile privatisations seven years earlier – went into administration after the Hatfield train crash and a botched modernisation of the west coast mainline. In 2002 the company was effectively nationalised by the Blair government – a policy approach supposedly discredited and abandoned in the 70s – and became Network Rail.

Meanwhile, the short-term British business culture identified by Will Hutton persisted. Investment by companies fell almost continuously between the late-90s and the late-00s. With trade unions weak, many employers became meaner. “Around 2003, wages for most Britons started to flatline,” says Will Davies. This was usually a sign of a recession rather than a boom, and had not happened since the early 80s. In order to keep shopping, people borrowed: outstanding private debt, already high by international standards in 2003, at about twice the national GDP, began rising, faster and faster, towards a peak of more than two-and-a-half times GDP in 2008.

“Much of the apparently benign [economic] growth … did not in fact represent a sustainable expansion,” wrote the economists Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato in their introduction to the 2016 book Rethinking Capitalism. “Rather, it reflected an unprecedented increase in household and corporate debt … lax lending practices … [and] an asset price bubble, which would inevitably burst.” Large elements of the neoliberal British economy were going to prove unsustainable.

I

n Dagenham, on the eastern edge of London, the local Labour MP Jon Cruddas noticed pressures building. The area has some of the cheapest housing in London – worn but sought-after 1930s semis – but “around 2002, 2003”, Cruddas says, “the economic status quo stopped working: wages, property prices, competition for public services … People were not living the lives they had been promised by the politicians.” In 2007, he stood for the Labour deputy leadership.

Cruddas was (and is) on the left of the party, but had a reputation for free thinking and building unexpected alliances. After working in Downing Street in the 90s, and helping introduce the minimum wage – one of Blair and Brown’s few alterations to the economic status quo – Cruddas had become frustrated by their refusal to confront corporate power. He based his deputy leadership bid around attacks on “free-market dogma”, and warnings about “the material insecurities” and proliferation of low-skilled jobs in his and other working-class constituencies. Once famous for highly unionised car manufacturing, Dagenham was becoming a patchwork of derelict former factory sites and casualised, low-paid work in retail. Standing against five other less radical, better-known candidates, Cruddas won the election’s first round. But subsequent rounds of voting narrowly eliminated him from the contest.

Regardless, the tempo of the revolt against free-market Britain picked up. The following year, the activist and thinker Maurice Glasman, whom Cruddas knew well, began to conceive of a movement he called Blue Labour. Glasman had worked for years with people who felt bullied by the modern economy, through the community organisation London Citizens. “I was just channelling what I was hearing,” he says. “People would say to me, ‘I’ve got to work two jobs to survive,’ or ‘I’ve had to move to London to find a job, but my mum is in Derby and she’s dying.’”

A social conservative, Glasman saw capitalism as “a criminal, dominating thing” that fractured families and communities. Glasman is an intense, compelling talker, and as with Will Hutton a decade earlier, his ideas intrigued senior New Labour figures, many of whom were becoming more interested in the importance of community themselves. But when he properly laid out his critique of capitalism, he remembers, “their faces would go a bit blank. Then they would say: ‘You don’t understand. It’s the goose that lays the golden egg.’”

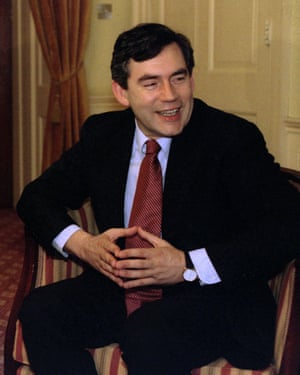

Along with close allies such as Ed Balls, Brown saw the deregulated City of London as a source of tax revenue to fund more generous state spending. During his premiership from 2007 to 2010, despite the City’s major part in causing the 2008 financial crisis, Labour could never quite bring itself to turn against the free-market capitalism it had inherited and furthered.

Instead, improbably, the denunciation came from the right. Phillip Blond was a conservative philosopher and theologian with a declamatory, slightly old-fashioned persona and prose style who had lectured for years at a small Church of England higher-education college based in Cumbria and Lancashire. In 2008, he began publishing newspaper articles attacking the Thatcherites and New Labour as co-conspirators. “The lesson of the last 30 years,” he told Guardian readers in May of that year, “is that neither the state nor the market is able to alleviate poverty or deliver opportunity for all.” Cleverly branded as Red Toryism, Blond’s ideas caught the attention of David Cameron. He was then still a relatively new Tory leader, and was energetically and shamelessly looking to differentiate his approach from Thatcherism.

In January 2009, Blond wrote much of a speech that Cameron delivered to the annual summit of the global business elite at Davos. “This is what too many people see when they look at capitalism today,” declared the Tory leader, who had until recently been an enthusiastic free-marketeer himself. “Markets without morality … wealth without fairness … recklessness and greed … lives [that] feel like little more than flotsam in some vast international sea of business.”

Cameron’s solution was almost laughably vague and ambitious: the creation, by unspecified means, of a new “capitalism with a conscience”. But he and Blond caught a mood. Thanks to the financial crisis, during 2008 and 2009 Britain suffered its worst recession since the calamitous first years of Thatcher’s market experiment in the early 80s.

In 2010, as Brown’s government ended and Cameron’s began, Westminster was suddenly crowded with competing critiques of the free market. As well as Red Toryism and Blue Labour, there was “fake capitalism”, an idea promoted by the Conservative MP Jesse Norman. It said that, in Britain, corporations lived too easily off earnings from privatised state functions. There was also a run of acclaimed books about the costs and flaws of neoliberalism: The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in 2009, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism by Ha-Joon Chang in 2010, and The New Few: Or a Very British Oligarchy, published in 2012 by Ferdinand Mount, who in the 80s had been one of Thatcher’s senior advisors. And over the winter of 2011-12, there was Occupy London, a raucous anti-capitalist encampment outside St Paul’s Cathedral. During its first weeks, Occupy London received strikingly plentiful and respectful media coverage.

The culmination of all these revolts, some hoped, would be the party leadership of the one senior New Labour figure who had never been fully converted to the free market, Ed Miliband. “When Ed and I worked for Gordon at the Treasury,” says the Labour peer Stewart Wood, who became a Miliband advisor, “we used to sneak off for a drink at the end of the day, and say to each other, ‘Why isn’t the government doing anything to challenge the market?’”

Miliband unexpectedly won the Labour leadership in 2010, after campaigning against “brutish US-style capitalism” and for a more controlled, egalitarian British economy. As leader, he consulted Hutton and Glasman, whom he made a Labour peer. He appointed Cruddas to lead a review of all Labour’s policies. And he made high-profile speeches attacking corporate “asset-strippers” and “predators”, the treatment of customers by the privatised utilities, and the worsening living standards of “the squeezed middle”. He condemned neoliberalism in more concrete terms than Cameron’s generalities at Davos.

Cruddas was energised: “We were beginning to change lanes as a party.” Even some of the small residue of older Labour MP’s who had never accepted any aspect of Blairism were intrigued. John McDonnell told me: “In some of his criticisms of the market, Ed Miliband was ahead of his time.”

But Miliband’s judicious, qualified critique of capitalism had to compete for political space with other, more primal forces unleashed or strengthened by the financial crisis: resentment of immigrants and the European Union; resentment of MPs after the expenses scandal, and of elites in general; and above all, Cameron’s appealingly simplistic austerity policies.

Even though the cuts in state spending made the daily experience of neoliberalism worse for many Britons – by weakening the initiatives introduced by New Labour to soften it – the rhetoric used to justify austerity helped make the general discourse about the economy more cautious, not more adventurous. Rather than talking about the bankers, and how to reduce their power, people increasingly talked about scroungers. The economic views of many voters initially moved rightwards, not leftwards.

With his modest communication skills, Miliband faced a huge task in advocating a different kind of economy. The few reforms he proposed were either too abstract and technical-sounding (“predistribution”, or creating a capitalism that requires less redistribution of income by government), or too short-term (a temporary price cap on energy bills) to form a coherent picture.

Like Blue Labour and the Red Tories, he wanted to remove the worst excesses of the free market while leaving the rest of it intact. The ambivalence of the Labour mainstream towards capitalism, an ambivalence as old as the party itself, “played out inside him,” says Cruddas. Last month, Miliband told the Guardian with a characteristically opaque mix of self-confidence and self-criticism: “I think what Jeremy [Corbyn’s success] teaches me is that when I had instincts that we needed to break with the past, and we needed more radicalism, I was right.”

In 2015, whatever Miliband’s true intentions, the many remaining neoliberals in the Labour hierarchy, such as then shadow chancellor Ed Balls, had other economic priorities. So, increasingly, did Glasman, who became controversially preoccupied by the idea that a reformed British capitalism would involve drastically less immigration. At that year’s general election, after an internal struggle that Cruddas and Miliband lost, Labour presented a manifesto that emphasised cutting the national deficit in language little different from that used by the Tories. The manifesto only criticised the deregulated capitalism that had effectively created that deficit in the first place in coded terms: “We will build an economy that works for working people,” it promised blandly. Even though more and more politicians and commentators agreed that free-market Britain was working less and less well, the anti-capitalist moment seemed to have gone.

B

ut even rigid, insular Westminster politics has to bend to economic realities in the end. In 2017, after two more years of thin growth and austerity, with British wages in their longest slump since the Napoleonic wars, and home ownership at a 30-year low, neoliberalism is no longer producing enough winners to be an utterly dominant set of political ideas. An opportunity has been created – bigger than any before – for the anti-capitalist counter-revolution that has been stopping and starting since the mid-90s.

Phillip Blond senses it. “I go into No 10 [Downing Street] a lot,” he says. “They really do get it about the failures of the market.” Glasman has been to No 10 in recent months too. “There is a stirring among genuine Conservatives,” he says. “A realisation that capitalism is against place and home.”

Cruddas quite liked the 2017 Conservative manifesto: “Some of it was very well written. I thought: ‘Spot on. Confront the market. Make government more interventionist.’ It was an attempt to acknowledge that the world is now challenging the old Thatcher certainties.” But he liked the Labour manifesto a lot more. “It has set up the possibility of … a different kind of economy. There are more continuities between the manifesto and Ed’s than people assume, but under Ed we had to smuggle our anti-free-market stuff in. It wasn’t spoken to properly. Corbyn and McDonnell are more explicit. Some of the people and energy from the anti-globalisation movement of the 2000s have fed into [the pro-Corbyn movement] Momentum. And some of the concerns of those activists are being reconciled with the economic concerns of people here, in Dagenham. Everything’s in play. It’s fantastic.”

In early July, not long after Labour’s far better than expected election performance, I went to a party rally in Parliament Square. During the 90s and 00s, I had been there repeatedly for slightly sparse anti-capitalist demonstrations, which felt, at best, defiant. But now the atmosphere was expectant. “We are winning, and the battle is now on our terms,” said one of the warm-up speakers, to a mass of young and much older faces – the potent Corbyn electoral coalition made flesh. McDonnell made a short, fierce speech attacking “the bankers and profiteers” and “neoliberal trickle-down economics”. He ended with a promise: “Another world is in sight!”

Afterwards, I asked him why it had taken so long. The financial crisis began exactly 10 years ago this month. “When a crash occurs, people are in survival mode,” he said. “It’s when growth returns that people get angry.” What did he think of the Conservatives’ apparent break with the free market? “The Tories are opportunists.” Then he talked fluently for several minutes about Labour’s plans to “learn from Germany” about how to create a more high-tech, more long-term economy. It sounded like a passage from The State We’re In. With his neat silver hair, and wearing a striped shirt with a bright summer jumper slung over his shoulders, McDonnell even looked like an off-duty German industrialist.

But wasn’t he meant to be interested in replacing capitalism rather than reforming it? He gave a big, knowing smile. “It’s a staged transformation of our economic system.” Then he continued less gnomically: “Public ownership. A fairer distribution of wealth than in Germany. A society that is radically more equal … ”

Even economic thinkers close to McDonnell wonder if a Corbyn government could effect such a transformation. Paul Mason, author of Postcapitalism, says: “They have a big task with a small team. We face problems – climate change, information technology destroying jobs, a market economy that in many sectors is not capable any more of generating value – that were not faced by Keynes,” the last economist to shift British capitalism to the left, more than 70 years ago.

Mazzucato is probably McDonnell’s favourite contemporary economist. In her much-cited 2013 book The Entrepreneurial State, she argued convincingly – as the Labour manifesto did – that through state-funded research and other investment, government acts as an essential accelerator of capitalism rather than a drag on it, as free-marketeers usually claim. Last year, she gave the first lecture in an ongoing series of Labour events intended by McDonnell to set out a “New Economics”. According to the website LabourList, “McDonnell sat [in] rapt attention throughout.”

In a hot meeting room at University College London, where she is director of a new institute for innovation, the Italian-American Mazzucato told me that the 2017 Labour manifesto was “a turning point” in British economic policy, “full of good stuff, a new energy”. She advises McDonnell. Yet she also advises the Conservative business secretary, Greg Clark, and the SNP. She thinks Labour could do better: “I say to them, ‘You sound defensive. You sound like you know what’s wrong with the economy, rather than what could happen.’” She says Labour needs to explain its economic policies more compellingly: “When you do bold things, if you don’t have the language to describe them, you’re going to be in trouble.”

The Conservative reformers of British capitalism have the opposite problem. So far, their rhetoric dwarfs their solutions. “Their promises to put workers on company boards, to stop high executive pay, haven’t really gone anywhere,” says Tim Bale, a leading historian of the party. Many observers, on both the left and the right, interpreted the 2017 Tory manifesto’s anti-market talk as solely a ploy to attract Labour voters – a ploy that failed so badly that it led to the resignation of one of its devisers, Theresa May’s joint chief of staff Nick Timothy.

Blond insists that many senior Tories besides Timothy oppose neoliberalism. Before Thatcher, there was a recurring Conservative impulse to soften capitalism during hard times – from the future prime minister Harold Macmillan’s influential 1938 book The Middle Way to Edward Heath’s centrist government in the 70s. But that impulse has weakened. “Most Tory MPs are Thatcher’s children,” says Bale. “Most Tory thinktanks are still in a free-market phase.” So is the Tory press: “I could more easily imagine an asteroid hitting the earth,” says Mason, “than the Sun and the Mail coming out for state intervention.”

Many Tory activists and voters have also become free-market diehards. During the election, when the usually revered editor of the website ConservativeHome, Paul Goodman, told readers “to get over Thatcher” and embrace the Tory manifesto, because “the world has moved on”, the response was prickly. One post accused May of being “a Labour sympathiser”. Another pointed out that Heath’s policies failed.

Moreover, the current government might respond to Brexit – an even bigger economic shock than Heath suffered in the turbulent 70s – by becoming more neoliberal, not less, having freed British business from the EU’s limited restrictions on capitalism. Tory economic policy has swerved suddenly rightwards before. Faced with the aftermath of the financial crisis, Cameron and his chancellor, George Osborne, quickly dropped Red Toryism and instead told Britons to toughen up for “the global race” – their phrase for an ever-more competitive capitalism. Osborne had never lost his faith in the free market. “Cameron turned out to be just a standard Thatcherite,” Blond now says.

As Cameron, the son of a wealthy stockbroker, knew well, Britain is still home to plenty of neoliberalism’s beneficiaries: hedge funders, homeowners with the right kind of property, disproportionately rewarded “top talent” from footballers to management consultants, and companies built on cheap labour and loose regulation. They will not give up their supremacy easily, and after Brexit, a Tory government – or a Labour one – might be desperate for economic growth from any source.

A

s an idea, the free market retains a simple power. “Neoliberalism was sold as capitalism perfected,” says Mason. That has made its diminishing returns politically explosive, but it has also made a reformed capitalism hard to sell. “The idea that markets work well in very limited circumstances, that economic life is about compromise, imperfectability – that’s not an argument you can present easily in a tabloid or a political advertisement,” says Abby Innes, assistant professor of political sociology at the London School of Economics.

Critics of neoliberal Britain have long dressed their texts and speeches with rosy images of other countries’ kinder economies. “Following the successful example of Germany and the Nordic countries,” says the 2017 Labour manifesto, “we will establish a National Investment Bank … that unlike giant City of London firms, will be dedicated to supporting inclusive growth.” In today’s spivvy Britain, how grown-up and enlightened that sounds. But on reflection, the idea that Britain should become more like Germany – its profoundly different capitalism the product of a different geography, culture and history – feels both very ambitious and yet also underwhelming. Can’t we come up with our own economic vision?

Somehow, it would have to reconcile the intensely competitive, commercialised daily existence of many Britons with the fact that the economic system that created that individualistic world no longer works very well. But perhaps the children of Thatcher’s children have an answer. Many of them are already living with this tension: working ambitiously but often for nothing; sharing living space and possessions as well as racing to buy them; jostling with each other for the smallest economic opportunities, but also marching together for Corbyn.

The emerging outline of a new economic order is often present, not much noticed, amid the final stirrings of the old. In the 70s, the City traders and sharkish entrepreneurs of the Thatcher era to come were often already at work, even as trade unions and Keynesians still held court in Downing Street.

If Brexit proves a disaster, or another crisis soon hits our largely unreformed financial system, as an increasing number of commentators predict, the political space for alternatives to neoliberalism may open further. But Glasman predicts that working out exactly what comes after modern British capitalism will be “the job of the rest of our lives”. He is 56 years old.

Main illustration by Jasper Rietman

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario