Five single men share why they've struggled to find women worth dating

They ask if it is possible to find considerate women who don't want to rush things

One psychotherapist blames online dating and pornography for complications

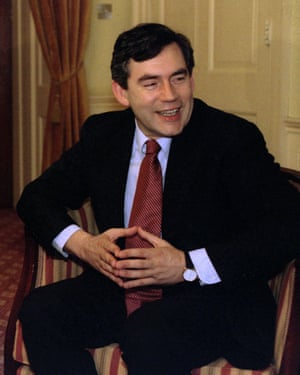

He is what you might call, with some understatement, a catch. Chris Gray, 57, is tall and attractive with dark hair and blue eyes.

By his own admission, he is ‘very well‑off’, owns several properties, including a £1.3 million terraced house in affluent Chiswick, West London, and is financially set for life, thanks to a series of successful investments.

A widower, Chris is educated and well‑travelled — in part thanks to his previous career as a BBC cameraman of 30 years’ standing.

The cherry on the cake? For hobbies, he flies small aircraft and enjoys dining in Michelin-starred restaurants.

Five single men shared why they've struggled to find women worth dating. Chris Gray, 57, (pictured) says 'I’m all for female equality, so why do 99 per cent of women expect me to always foot the bill'

So why, you might wonder, has Chris joined the growing band of British men, old and young, who have sworn off women for ever?

It’s simple, he says. There simply aren’t any good women out there.

‘I have given up. I have many female friends, but I can’t be bothered to deal with all the hang-ups and complications other women have,’ he says.

‘Often, at my stage in life, many of them are divorced and seem full of bitterness and anger.’

That’s certainly not the only complaint single men such as Chris direct at potential female partners they meet.

Indeed, after the Mail recently recounted the stories of attractive single women who appeared to have everything, yet said they still couldn’t find a decent man, there was a significant backlash from male readers.

Men told us in their droves that it wasn’t they who were to blame — but women.

They insisted romances failed today, not because of male laziness and a lack of attention to their physical appearance as claimed, but because women are picky and demanding divas, who either treat dates like job interviews or are all too keen to leap into bed.

Above all else, though, men said women are increasingly status and money-obsessed. While they might be full of the entitlements of feminism and happy to preach the necessity of equality, men said the opposite sex were simultaneously all too keen to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle almost entirely paid for by their male partners.

One MailOnline reader put it succinctly in response to the article’s question asking why women were finding it so difficult to find a man with whom to settle down: ‘It’s because every man they meet has already been taken for a ride and had his pockets emptied.’

So should the old adage ‘Where have all the good men gone?’ really be more applicable to women instead?

Chris is adamant this is the case —and believes single, middle-aged women in particular should look closer to home when casting blame.

You might want to dismiss Chris as just another misogynist. Far from it.

Alex Cavadas, 41, (pictured) a divorced part-time actor, says he’ has given up on love after a series of emotionally crushing dates with women seemingly after just money

A devoted husband of 21 years to his late wife Rosie, who also worked in television until her sudden death from an undiagnosed heart condition in 2008, the urbane Chris is as removed from a stereotypical knuckle-dragging woman-hater as you could hope to meet.

Yet even he was astonished by how brutally mercenary some of the middle-aged single women he met were.

‘I was brought up by just my mother and absolutely support female empowerment. But the vast majority of women I met expected the man to pay for everything,’ he says. ‘I’m all for female equality, so why did 99 per cent of women expect me to always foot the bill?’

Chris’s dating experience was particularly bruising as he spent years grieving, before loneliness led him to online dating and to pay a substantial sum to an introduction agency to find someone with whom to share his life.

But as well as being relentlessly focused on money, he found some of the women he met — and he went on scores of dates — were surprisingly envious.

‘A few years after Rosie died, I felt capable of trying to meet someone, so I joined the brutal triage of online dating. It was such a disappointment. I found women can be so jealous. They very quickly started to make demands. They were jealous of my female friends. Believe it or not, some didn’t like that I had photos of my wife still on the wall.’

In addition, many were hell-bent on commitment, treating casual lunch dates more like job interviews for a prospective husband.

There was a gradual realisation that you are complete just as you are. Men can have an entirely content life on their own

Chris Gray

‘The introductory agency set me up on a date with an attractive lady in her 50s who had a very powerful job. She texted me, saying she was on her way and to ask for my address so she could park on my street.

‘Minutes later there was a knock on the door. She barged in and started looking around: checking me out, checking out my house. She was a complete stranger to me. It was very odd.’

He says after lunch — which, of course, he paid for — things went even more rapidly downhill.

‘She said: “So, Chris, what about us? Where are we?”

‘I said: “We’re on a first date, I don’t know.”

‘Women like this are trying to run before they can walk. Maybe, faced with mortality as we all are in our 50s, she was so desperate for a relationship she tried to rush things.’

Chris found he differed from many women he met because, unscarred by the trauma of a divorce, he had none of the resentment that seemed to haunt others. Indeed, he was driven by the loving memories of how wonderful life can be when you have a partner with whom to share it.

‘I loved — love — my wife. I always will. My marriage was very happy. Maybe I was trying to recreate that, but it certainly didn’t work.’

After around five years of dating, in 2015 Chris decided enough was enough.

‘There was a gradual realisation that you are complete just as you are. Men can have an entirely content life on their own.’

Ross Foad, 29, (pictured) has been single now for more than two years and says: ‘This is what I want for the rest of my life'

So what’s causing this schism between the sexes at the very point in their lives when you might imagine they would be more likely than ever to settle down?

Psychotherapist Teresa Wilson, who runs a practice in South-West London, believes men and women are coming to the dating game in middle age with entirely different perspectives.

While women — now so independent in outlook and behaviour — are much less worried than male counterparts about finding a new long-term partner, men are more likely to have come from a relationship they’d rather have kept.

‘Women don’t feel quite so trapped in bad relationships. They’ve found a certain liberation over the last 20 years,’ she says.

‘Men, however, like the stability of a home life provided for them, their creature comforts, and often don’t know how they’re going to manage except by going into another relationship.

‘Women, meanwhile, are not as fearful [of being alone]. They tell me: “I might find another relationship, but even if I do not, I can cope.” ’

Meanwhile, Selena Dogg-ett-Jones, a psychosexual and couples’ therapist, sees men as less able to cope with an entirely new dating landscape which has made singletons much pickier about prospective partners.

‘If you’re newly divorced, the dating game has changed dramatically; it’s all online now,’ she says.

‘People who had finished a long-term relationship or were widowed used to be introduced to someone new at a dinner party.

‘But today people will say precisely what they want online. For example, “I only want to meet someone between 40 and 50”, meaning someone aged 51 will not be considered because they’re not in the right category. If they met someone for real, they’d maybe not find out their age until they’d been on a couple of dates, by which time they’d probably like them and the age wouldn’t matter.

‘But instead, all they’re looking at is a photograph and they’ll swipe or click “yes” or “no”. It’s very difficult.’

Alex Cavadas, 41, a divorced part-time actor, says he’s a victim of this pickiness — and has given up on love after a series of emotionally crushing dates with women seemingly set on just one thing: money. ‘Some of the women I’ve dated were too pushy,’ he says. ‘One woman talked to me on the first date about having children and getting married.

‘She asked me how much I make, which is about £400 a week. She told me that wasn’t enough, saying: “I have certain standards.”

‘Yes, I’m a struggling actor. But she wasn’t well off, either. She was an au pair. She was just looking for a wealthy husband.

‘She told me she thought I was handsome and kind, but not successful or rich enough.’

For Alex, who lives in Mitcham, South London, it has been heartbreaking to find his hopes for love so quashed, especially because he says he was very happily married until recently.

‘I met my wife at a concert in 2004 and we married a few years later. I was smitten instantly,’ he recalls.

+8

'The dominant discourse in the Western world is that men are up for sex 24/7. But many men are not' says Alex (file image)

‘Things were great at first, but when our daughter was born in 2014, it felt to me like my wife didn’t want me any more. We divorced in 2015.

‘I’ve been on dates since then, but soon think to myself: “What’s the point?”

‘Since my marriage, I have been celibate because I can’t find a nice woman.’

Psychotherapist Selena says another reason for men, old and young, being disappointed by modern dating is that today’s sexual relationships have been complicated by online dating and pornography.

‘There’s an awful lot of instant sex expected with some of the apps, like Tinder. It’s meet-for-sex and sometimes it will develop into a relationship.

‘The dominant discourse in the Western world is that men are up for sex 24/7. But many men are not. They want to get to know the woman. They tell me they find it very difficult because they feel rushed; and women are rushing them because they think that’s what is expected. Some men can cope with one-night stands, but most do not feel comfortable with them.’

This is the case with Jamie Clows. He may only be 27, but he’s already decided to give up on women entirely, disillusioned after a number of painful relationships and subsequent attempts at dating women who, after drinking too much, have proved themselves rather too keen to jump into bed.

Jamie, a small business owner from Chesterfield, Derbyshire, who has a young daughter from a previous relationship, says he is ‘a lot happier being single’.

‘It all ends the same way,’ he says resignedly. ‘I don’t want to go on dates. It depresses me.

Jamie has found himself agreeing with a growing army of single men who make up the online community called MGTOW — Men Going Their Own Way (file image)

‘Some women have become violent, in jealous rages for no reason, because they’ve been drinking too much.

‘I’d rather go for a walk than to the pub. But I’ve found it hard to meet anyone the same as me.

‘Some women have asked me to sleep with them on the first night. They get drunk and wear very revealing clothes, too. I think women who do this don’t respect themselves, and I can’t respect them, either.’

Jamie has found himself agreeing with a growing army of single men who make up the online community called MGTOW — Men Going Their Own Way — which has tens of thousands of followers. On this website, disillusioned males come to share relationship problems, their struggles for equal access to children and describe being freer, happier and wealthier for shunning relationships.

The philosophy of MGTOW, which began in America in the Seventies, is described as a ‘statement of self-ownership, where the modern man preserves and protects his own sovereignty above all else’.

On its website, it lists great men throughout history — among them Beethoven and Sir Isaac Newton — who were all single and, as a consequence, says MGTOW, led fulfilled lives packed with accomplishments.

It’s a group Jamie admits he never imagined he would find kinship with: ‘When I was younger, I always dreamed I would get married. No more.’

Trelawney Kerrigan, a consultant for the Dating Agency Association, says: 'After a couple of knock-backs, [men] will shrivel up. They are easily disillusioned; women are better at brushing themselves off' (file image)

Ross Foad, 29, is another who subscribes to this philosophy. A talented actor, comedian and writer, he is charismatic, confident, fit and attractive.

But he says he has no interest in ever finding anyone with whom to spend his life.

For Ross, from Kingston-upon-Thames, south-west London, says: ‘I don’t hate women — I have many female friends. I just can’t give them what they want, which is commitment, attention and time. I want to concentrate on my career. I like to write, create films and be active.’

Ross has been single now for more than two years and says: ‘This is what I want for the rest of my life.’

Another factor, experts say, is that men are actually more sensitive than women, and struggle to deal with romantic knock-backs.

Trelawney Kerrigan, a consultant for the Dating Agency Association, says: ‘Women will take a more positive approach while men, after a couple of knock-backs, will shrivel up. They are easily disillusioned; women are better at brushing themselves off.

‘It’s a confidence thing with men. You often hear men saying there are not enough genuine people out there and nobody’s taking it seriously.’

Danny Webster, a 33-year-old radio presenter from Birmingham, who has been single for more than three years following the break-up of a long-term relationship, admits he’s given up on women because of painful rejections.

‘I think women don’t want nice men like me. They want bad boys,’ he says. ‘I’ve found the knock-backs hard to deal with and decided a few years ago I’m better off alone. I’m meeting more people of this mindset. Increasing numbers of men are choosing to be independent.’

However, Danny does admit he finds the fact he will not have children difficult to bear.

‘It’s one part of my life I yearn for, because when I see all my other friends with kids, I feel I should have them, too.

‘But there is no one holding me back. I can come and go as I please. A lot of men would give their right arm to have that freedom.’

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-4817380/Where-good-women-gone.html#ixzz4qmk6H12E

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook