How can we make facts matter? Research in psychology and political science offers a little hope.

Updated by Julia Belluz and Brian Resnick

/cdn2.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/51862891/621735548.0.jpeg)

Donald Trump made an “unusual degree” of blatantly false and misleading statements for a presidential candidate. And he won. Since then, we’ve seen the continuation of the pattern: On November 10, a day after the election, he insisted, with no credible evidence, that election protesters were paid actors. On Sunday, he described elements of his first 100 days’ plan — the deportation of 3 million “illegal immigrant criminals” — that are, as Vox’s Dara Lind has reported, based on faulty statistics.

This track record doesn’t portend an era of truthfulness at the Trump White House. And many are questioning if facts are under genuine assault. NPR's senior VP of news, Michael Oreskes, recently reminded listeners, “Our first principle is that facts exist and that they matter.”

But Trump was actually just trading on something psychologists and political scientists have known for years: that people don’t necessarily make decisions based on facts. Instead, we are often guided by our emotions and deeply held biases. Humans are also very adept at ignoring facts so that we can continue to see the world in a way that conforms to our preconceived notions. And simply stating factual information that contradicts those deeply held beliefs is often not enough to combat the spread of misinformation.

The map is fake. The story is incredibly misleading. And it's spreading like crazy all over Facebook.

If we want to try to fight the spread of misinformation, we first need to understand why we’re wired to be so gullible.

1) Partisan bias skews our perception of the world

When we’re part of a group, our brains like to see that group in a positive light. In lab experiments, when researchers randomly assign people to teams, almost immediately participants will start to like their teammates better than the other guys. It’s almost instinctual, unthinking. It’s thought that group identities quickly become part of our individual identities. That’s why when you see a hate group burn your flag, it feels like a personal insult. Similarly, when a fact is hostile to our group, we’re keen to avoid it.

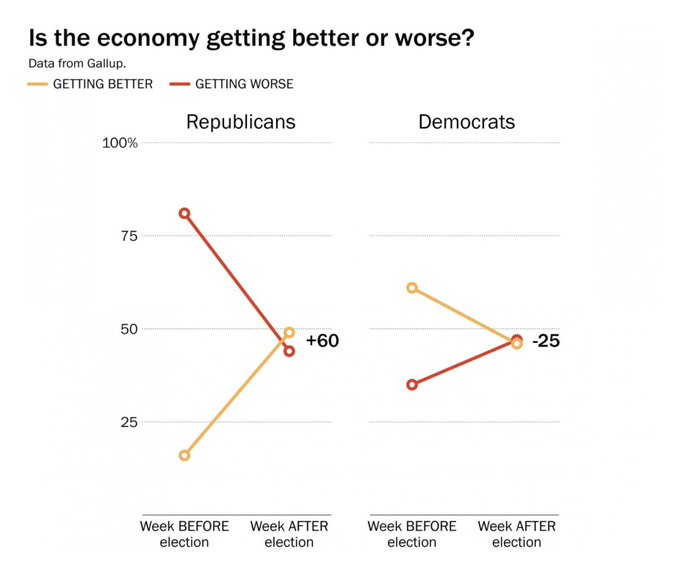

Here’s an amazingly clear example of that. It’s partisan bias in one chart.

wow... that must've been some weekend. http://wapo.st/2geyAHe

In just a week before and after the election, Democrats and Republicans flipped their opinions on the current situation of the economy. The economy didn’t change that drastically in a week. And studies constantly find this: People don’t answer questions about the economy based on scholarship and objective information. They answer in a manner that benefits their political team. And as you can clearly see above: Yes, liberals do this too.

2) We seek to confirm our preconceived conclusions and are dismissive of the facts that threaten our worldviews.

Our number one bias is to make ourselves feel good. It just feels bad to be wrong, to lose. So we avoid it at the cost of reckoning with the truth. Psychologists call this “confirmation bias” — we seek facts to support the ideas we already believe to be true. “Most Americans are not paying attention to data, and even people who should be tend to discount it when it doesn’t fit their expectations,” Ingrid Haas, a political psychologist at the University of Nebraska Lincoln, explains in an email.

When people do pay attention, they’re more and more likely to seek out news sources that conform to their worldview. (Cable news and Facebook have made this easier than ever.)

3) Emotions resonate more strongly than facts

Evidence continues to mount that political sensibilities are, in part, determined by biology. These inborn sensibilities create our "moral foundations." It's the idea that people have stable, gut-level morals that influence their worldview.

Politicians intuitively use moral foundations to excite like-minded voters. Conservative politicians know phrases like "Make America Great Again" get followers' hearts beating. They’re reacting strongly to the idea of protecting the country. To them, it’s a feel-good, positive thing. Don’t try to tell them otherwise.

Trump is especially good at tapping into fear, a particularly motivating emotion. Studies findwhen white people (any white people, even liberals) are reminded that minorities will eventually be the majority, their views tilt conservative. A recent experiment showed that this reminder increased support for Trump. Which doesn’t mean all white people are racist: It means fear is an all-too-easy button to press. We fear, unthinkingly. It directs our actions. And it nudges us to believe the person who says they will vanquish our fears.

It doesn’t help that there’s more misinformation than ever before

Besides our fallible brains, there’s another big reason facts can be insignificant: The internet and social media make misinformation that reinforces our beliefs easier to access and more visible.

"We select the things to hang on a wall, sources to listen to,” said Michael Lynch, a University of Connecticut philosophy professor and author of The Internet of Us: Knowing More and Understanding Less in the Age of Big Data. “That means people can experience this sort of sense of the ground moving underneath them — like when liberals woke up and realized Brexit had happened."

This is particularly true for the politically engaged, particularly in this time of polarization. As Vox’s Tim Lee reported, researchers at Facebook found liberal-leaning Facebook users are more likely to see liberal articles in their newsfeeds, while those with conservative affiliations see more conservative articles.

"Partisanship and ideology haven’t just become more polarized but also better sorted," Dartmouth political science professor Brendan Nyhan pointed out. "So Democrats are more likely to be liberal and Republicans more likely to be conservative, and they tend to associate with people like them, which may prevent them from getting exposed to different kinds of information on the margin."

This state of affairs is fueled by the fact that the traditional gatekeepers of public information — big newspaper outlets, nightly news broadcasts — no longer wield as much influence.

"Politicians have responded accordingly" by reaching out to audiences directly through blogs and social media campaigns, Nyhan said. This can help fuel our biases, reinforce our beliefs, shut out opposing views — and perhaps make us more gullible.

And not only are the like-minded gathering together on social media but there’s also evidence to suggest that whole communities are becoming more ideologically unified in our hyperpartisan age. We’re further apart than ever before, both virtually and physically.

The research on how to make facts matter is scant, but hopeful

To be honest, we’re not entirely optimistic that facts will ever thrive in 21st-century America. Academics are pessimistic too.

“So long as we are all immersed in a constant stream of unbelievable outrages perpetrated by the other side, I don’t see how we can ever trust each other and work together again,” psychologist Jonathan Haidt recently told Vox’s Sean Illing. “We have to recognize that we’re in a crisis, and that the left-right divide is probably unbridgeable.”

The world we live in is simply structured to amplify our divides and, in doing so, make us more psychologically resistant to inconvenient facts.

For facts to matter more, we need environments that incentivize truth telling — ones that give us rewards for truth telling, and where lies are costly to us personally. That a man with as flimsy of a relationship to the truth as Trump can win a presidential election goes to show that fibbing is a winning strategy. If evolution theory can be instructive, it would tell us that the winning strategy will come to dominate the environment.

So how can we change the environment to harken the evolution of a world where facts matter? Researchers have found that it is possible to foster that kind of environment, at least in theory.

In one experiment, when researchers paid political partisans to be honest, they were more likely to answer questions about the country and the economy correctly. And for politicians to care about being called out on lies, there has to be a credible threat that it will hurt their reputation.

There’s also some work that suggests that if people affirm their individual identity over their group identity, they’ll feel more free and willing to go against the group and embrace facts that would otherwise seem hostile. But it’s hard not to believe that our group identities and differences are more salient and un-ignorable than ever.

Fact-checking websites can also help, particularly when the fact-checking comes with a consequence.

"In some cases, fact-checking can backfire, particularly with people who are resistant to the information in the first place," Nyhan’s research collaborator Jason Reifler said. But, he added, "some of our other research shows the public does benefit from fact-checking."

In another small study, Nyhan and Reifler found some evidence that down-ballot candidates who were sent letters reminding them "politicians who lie put their reputations and careers at risk, but only when those lies are exposed" were somewhat more truthful in their campaigns, as measured by newspaper fact-checks.

Facebook is starting to take some action on its fake news problem. Some 40 percent of Americans read their news on Facebook. It would be extremely meaningful if facts were incentivized there. But Facebook is just a start.

Facts need a champion more than ever.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario